ORGANIZATIONS FOR RURAL COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT

IN THE Colonial period, organization by farmers was occasional and temporary, chiefly for defense against Indians, or for the larger operations of agriculture, such as harvesting. Between 1869 and 1889, it existed mainly for the purpose of regulating, through politics, the business of other people, in order that monopolies and middlemen should not exploit the profits of the soil. Since 1889, it has assumed a somewhat new character, and, leaving politics to politicians, has bent its attention on its own business—not merely increased crop production, but buying, selling, storing, and transporting. Combined

with these large economic programs, it has always had an educational and a social mission of great value, particularly in the small local units or clubs.

Local Associations

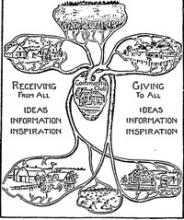

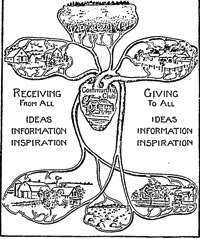

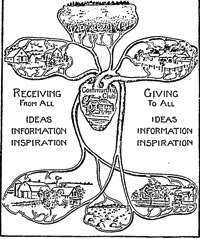

It is, in fact, these local associations which are doing the most effective work in making the countryside sociable and attractive. It might be said that they have in charge the educational and social life of the American farm, although the widespreading network of local and Federal government agencies now operating in the country has drawn to itself many of the tasks which were once performed by voluntary associations; consequently, these latter have become cooperating forces instead of pioneer influences. Their strength, however, is increased by this fact. It matters little whether they are only local or are local units of state or national organizations; in every case they exist for the purpose of making life in the home more efficient with less labor, in the community more attractive.

Farmers’ clubs. So-called farmers’ clubs include the entire family in their membership. They hold all-day sessions which are devoted to farming and farm-home problems, but are enlivened by music, recitations, debates, and and life dramatics by local or imported talent. The noon intermission is a great event, and includes a large dinner. In most cases, each club is an entirely independent body; but in certain states, Michigan, for instance, the individual clubs are federated into the State Association of Farmers’ Clubs. In 1908, no fewer than 120 clubs from 32 counties were included in this federation, with a membership of over 7,000. An annual state meeting of delegates is held.

Farm women’s clubs. Farm women’s clubs are strong influences in the new housekeeping and home-making. Many of them confine their programs almost entirely to housekeeping problems, the care of children, and the earning of pin money; others are more literary in their scope; and still others become travel clubs, assisted by the cheap prints of famous places, sold at a low price by publishing houses. Food is always an important part of the programs.

Boys’ clubs. Boys’ clubs are of value in turning to account the energies and talents of youth, which are often wasted when not organized. Boys under 14 years of age need a young leader who inspires hero worship. A secret and a badge add greatly to the spirit of fellowship. The drafting of a constitution and the formal election of officers is a good lesson in government. The regular meetings should never be invaded by grown-ups; but the entertainments, debates, and athletics which are open to the public will welcome the cooperation of parents and friends, and may be mighty influences in promoting sympathy between 2 generations. So organized, the boys will enter heartily into community-improvement work.

Girls’ clubs. Girls’ clubs are of value in creating the good homemakers of the approaching generation. They put fun and pride into labor, and teach the joy and beauty of friendliness. Girls who have been members of these clubs will be better wives and mothers than they could have been without that training.

Young people’s clubs. After boys and girls are 18 years of age, they can work together for all sorts of good things. Dramatics and pageants which illustrate local history can be staged by them, and exhibits of historic heir¬looms have often promoted a local pride which has found expression in better home institutions and better citizenship.

Parent-teacher associations. Parent-teach- er associations are doing a splendid work in bringing home and school into sympathy and cooperation. Every neighborhood ought to have one, and the mothers and fathers should meet with the teachers at least once a month during school term, and find out how they can help them. They should make the teach¬ers welcome in their homes, and aid them in becoming familiar with the work and problems which the children encounter out of school. Neither home without school nor school without home can educate children. The two must join hands with the children in the center.

National Organizations with Local Units

The Grange, or the Patrons of Husbandry. The Grange is a great national secret order. We know and love it best in its local groups, called “Subordinate Granges”; for these are community associations, made up of men, women, and young people over 14 years of age, who live in the same township or within a radius of 5 or 6 miles of one another. They are naturally bound together by a oneness of interest; for, to a great extent, they are all doing the same kind of farming, living in the same kind of home, and seeking the same kind of education and enjoyment. Beyond this, they are united by secret ritual, signs and passwords. The effect is to introduce a new tie between members of the same family (for membership frequently includes an en¬tire household); to show neighbors how many things they can enjoy together; to speed up community efficiency; and to direct education and amusements toward real community needs.

The importance given by the Grange to woman’s judgment and work has a very positive influence in extending her usefulness. It gives her an increased respect for her tasks at home'and an active interest and influence in community betterment. Four offices in the Grange are necessarily filled by women, and others may be filled by them. That of lecturer in the Subordinate Granges is frequently held by a woman. Whether man or woman, the lecturer is charged as follows: “In selecting subjects, include the household and the home. A well-ordered household is essential to a happy home, and without a happy home, no farm is fully a success.” With this idea in view, the National Grange has a home-economics committee; and the National Lecturer has prepared a handbook to aid the subordinate lecturers, in which is included home-economics work. Members of the Granges do well to qualify themselves for lecturing along household lines; they may also ask state colleges and other institutions to cooperate with them by supplying speakers. In line with this work, Subordinate Granges have greatly enhanced women’s exhibits at state and county fairs by practical and helpful demonstrations of the home arts.

At each meeting of the Subordinate Granges, after the ritual is completed and the business transacted, there follows a program, which has been arranged by the lecturer. This may include music, recitations, readings, debates, and serious discussions of local conditions and needs. It may be followed by a “feast” or, as is frequently done, the session may be divided into two parts, the feast form¬ing an excellent intermission, during which everyone is refreshed and stimulated by good food and by the exchange of ideas.

Meetings are often held in schoolhouses; and, when this is the case, an impetus is given to the valuable movement of making schools community-center meeting places. However, when Subordinate Granges are strong enough to erect their own halls, it is even better, for these are specially adapted to the social and educational life of the Grange.

How to establish a Grange. When it is de¬sired to establish a Grange, the best plan to adopt is to write for a copy of the “National Grange Monthly,” Westfield, Massachusetts, which will contain the name and address of the National Grand Master, who may be asked to send a copy of the last annual proceedings of the National Grange. This will give a list of the names and addresses of all the state masters. The master of the State Grange to which your Subordinate Grange will belong, will gladly cooperate with your neighborhood in every way, and will even send out organizers to start your work.

Pomona and State Granges. All the Sub- ■ ordinate Granges in one county often'organize into a larger unit, called a “Pomona Grange.” Pomona Granges have great monthly rallies, which comprise, as far as possible, the entire membership of the included Granges.

The State Granges are made up of delegates from the Subordinate Granges. They, as well as the National Grange, hold annual meetings only. Both of them are legislative and ex¬ecutive bodies and, considered by themselves, exert little social influence over the country¬side. They are, however, the fountainheads of business, and clearing houses for subor¬dinate activities.

Organization and history of the order. The Grange includes 7 degrees, the first 4 of which are conferred in the Subordinate Grange. The fifth degree is given in the Pomona Grange, the sixth in the State Grange, and the seventh in the National Grange.

The history of the Grange follows closely the development of farming as a science and a business since the Civil War. It has been the friend of almost every reform that has benefitted the farmer and his family since 1868. The study of its struggles and achievements might become with profit a part of the educational programs of Subordinate Granges.

The Farmers-’ Educational and Cooperative Union of America exists principally to regulate the business interests of farming. It is a secret order, exerting tremendous local influence, and possessing vast interests in fertilizer plants and in machinery and guano factories. By means of these Union-owned industries, localities are able to establish agencies for buying and selling in bulk, thereby driving to the wall small merchants as well as the retail agents of large interests. The Unions have sometimes been accused of impoverishing extended districts in this manner; but, in defense, they point to the increased efficiency on the farms, and to the larger in¬comes of farmers which have resulted. They maintain, moreover, that they have not used this boycott except when forced to it by unfair treatment. They are arrayed against the mortgage and credit system, and against graft, ' and they own a system of cotton warehouses in every cotton-growing state.

The order was organized in Texas in 1902, to exist for 50 years. It speedily absorbed a number of those organizations which had sprung up in rivalry of the Grange. By 1906, it had Unions in every southern state and in some northern ones. The total number in the United States was 6,870, and new charters were being issued at the rate of 25 a day. In a few years, the membership reached 3,000,- 000; and it is still increasing, making steady- head way in the North. Its membership includes both sexes, and receives Indians. Separate Unions have been established by negroes. Bankers, merchants, lawyers, and members of trusts and combines which might prove injurious to farming, are rigidly excluded from membership.

The order cooperates with organized labor, and pledges itself to give preference to the products of labor which is organized, and that its leaders shall cooperate with those of labor in efforts for legislative and political justice. The American Society of Equity of North America. The local units of tfc;,s National organization have great independence of action. Members are expected to extend fraternal care to one another in illness and misfortune. Harmony and brotherly debate are urged for the settlement of quarrels and disagreements. Meetings are held in the open country, in towns, and in hamlets. Its influence is mainly in the grain-growing belt. It was incorporated under the laws of Indiana in 1902, and is not a secret order. It exerts a strong influence in determining the prices of farmers’ commodities.

National and State Organizations Without Local Units

The Dry-farming Congress. The Dry- farming Congress is an efficient association, holding yearly meetings with a large body of delegates. Its purpose is not only to make the “desert blossom as the rose,” but to en¬courage everywhere an agricultural practice which shall conserve moisture to the utmost.

American International Congress of Farm Women. The American International Congress of Farm Women, organized at Colorado Springs in 1911 as an adjunct or fellow body to the Dry-farming Congress, held a number of interesting annual sessions, one of them in Belgium, and several in connection with the Dry-farming Congress in our arid states. In 1914, it separated from the Dry-farming Con¬gress, in order to make clear its nation-wide scope, and met independently in 1915, but has been little heard of since that time. Its weakness lay in its lack of basic organization.

The Hartford Movement. The Hartford movement in Vermont owes its beginning to 100 influential men in Hartford township, who organized in 7 groups, to promote better farming, better schools, and wiser and more abundant recreation. Out of the movement, grew the Greater Vermont Association and the Bennington County Improvement Associa¬tion, which receives help from the United States and from the Grain Growers’ Association. Other Vermont counties have organized in a similar way. The movement has consolidated churches, and improved religious and social conditions in small towns. It car¬ries on summer conferences in the open country, and, with the churches as centers, it encourages extension teaching and correspondence courses'in modern agriculture and house¬keeping.

The Amherst Movement. This movement for the enriching of social life in a farming country, was started by President Kenyon A. Butterfield, of the Massachusetts State Agricultural College, situated at Amherst. Its special contribution is a 5-week summer school, which closes each year with a conference of agricultural educators and rural social workers. Although it gives attention to technical agriculture, its emphasis is laid on the problems of church and school and such subjects as organization, reading, and amusements.

County Fair Associations

These associations provide in each county local agencies which operate through the different districts, encouraging organization among farmers and farm women in behalf of better production and better homes. They cooperate with the colleges in extension teaching; and the colleges, in turn, furnish the associations with exhibits, judges, and demonstrators for their shows. The results of their work are seen in the county fairs; but it is in the effort which local groups put forth in producing and preparing their exhibits that the real educational value of the movement lies. The people of the different neighbor-hoods may or may not hold regular meetings; but they are sure to visit together, in order to compare the results of their work, be it farming or house¬hold arts. Under community-spirited teachers, too, school-children are organ¬ized, in order to prepare their exhibits of sewing, cooking, and carpentry.

The feeling has become almost universal that these associations ought to become permanent, like the farmers’ institutes, and not confine their activities' to the short seasons when fairs are held. There is a tendency to employ as fair-assoc’ation secretary a man who is not a mere clerk, but an able agriculturist with the spirit of leadership, who will encourage an all-the-year-’round association, with every locality constantly alert in the study and practice of better farming and farm homes, and with neighbors brought together in frequent meetings for the exchange of ideas and the benefits of team work. Local fairs held in the schoolhouses or community halls are an excellent side activity of the associations.